61. Understand founder equity dilution and how your decisions impact what you keep.

In this episode, I talk about dilution, the process by which your ownership in the company shrinks as you bring in investment. The decisions you make, and the terms you negotiate, can drastically alter your payout at exit.

This article is part of our series on startup fundraising.

How does dilution work?

When you raise money for your company, you sell off a piece of it, so you own a smaller fraction.

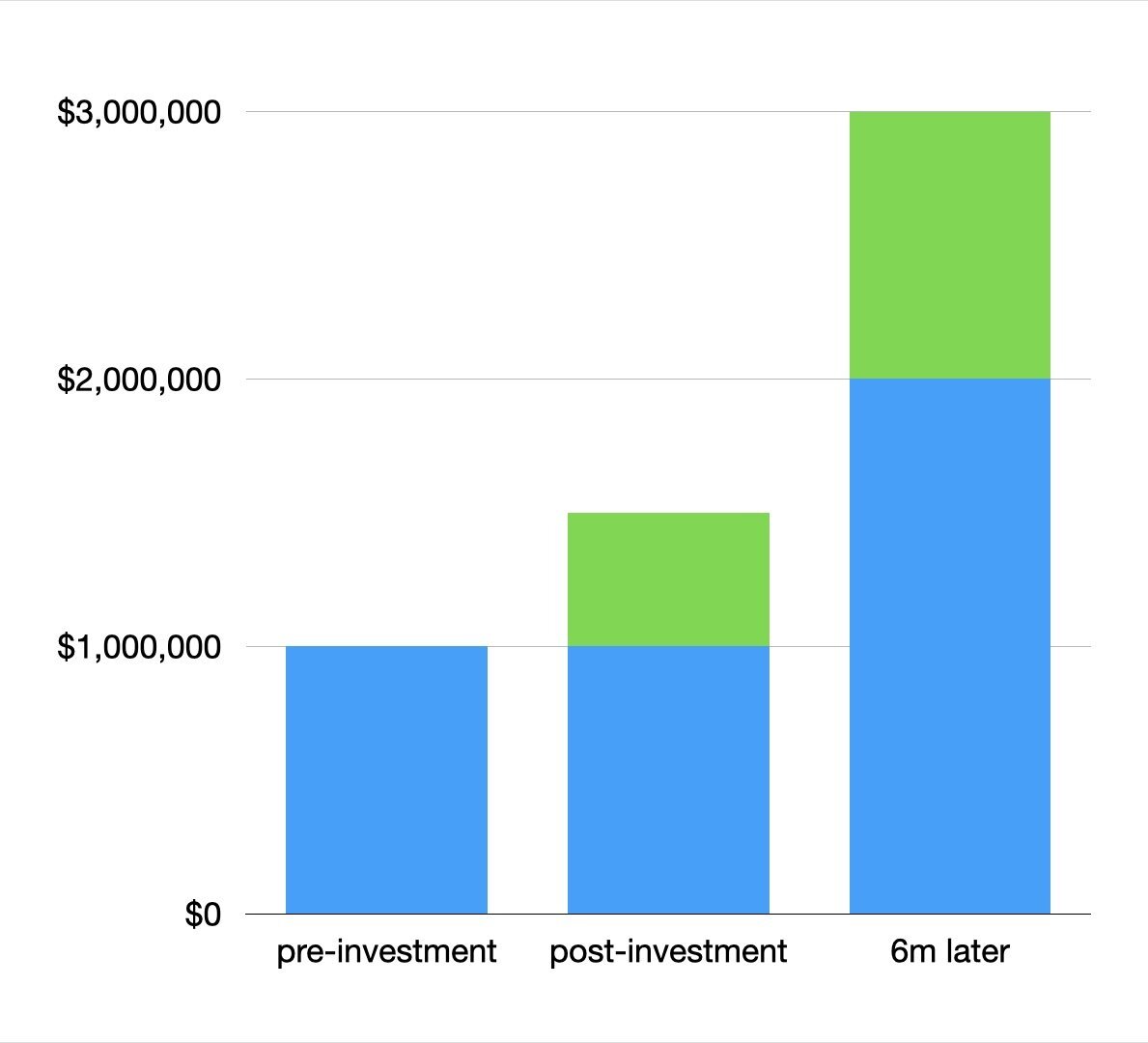

You do that by issuing new stock to the investors. Suppose your company is worth $1 million now, and you have one million shares of stock. Then the price per share is $1. If someone invested $500k, then they would be buying 500k shares. But those don't come from your stock; the company creates and issues 500k new shares for the investor to buy.

Post-investment, the company is worth $1.5 million because it was worth $1 million previously, and now it has $500k more in the bank. The value of your stock is unchanged.

The idea is that you will be able to take that new investment and grow the business, so the company's total value will increase. If you succeed, by the time you spend the cash, your piece of the company will be worth significantly more than it was before.

If you take several rounds of investment, you might end up with a narrow slice of the pie, but if the pie is gigantic, that can still be a very positive outcome.

How much ownership should you sell?

Typical investment rounds sell the new investors between 10 and 25% of the company, with the early rounds tending to take higher percentages.

Investor expectations for ownership create a somewhat circular relationship between valuation and the total size of the round. If you are raising a pre-seed round at a $3 million valuation, you would not want to raise more than $1 million to avoid excessive dilution, and the investor would ask for the round to be at least $500k.

Similarly, knowing how much money you need to raise can set a range for reasonable valuations. If those implied valuations are unrealistically high, that might mean you won't be able to raise that much.

In addition to the equity you sell in the round, investors expect you to set aside a block of shares for employee stock options. They will typically ask that you refresh that pool to between 10% and 20% of the total issued stock before each round, causing additional dilution to the current shareholders.

How much money should you raise in each round?

The answer is: as much as you need, but not much more.

Because Feel the Boot targets early-stage founders, you're probably thinking specifically about pre-seed or seed round. It's essential to get this right because early rounds are the most expensive money you will ever bring in. Because your evaluation is lower, each dollar an investor gives you will buy more of your stock and a bigger percentage of your company.

However, the worst sin you can commit is running out of money before hitting your next milestone and raising your next round.

If that happens, either you're going to fold, or you're going to need to take money under duress, which probably means a down round. In either case, the founders and existing investors take a beating.

At the same time, don't be tempted to go as big as possible because that just creates unnecessary dilution. You might find yourself raising an A-round already owning less than 50% of the company.

The Plug:

If you enjoy these blogs, please take a moment to join our mailing list Boot Prints. This low volume zero ads mailing list will alert you to new content, member exclusives, and give you access to free personal one-on-one coaching with me.

I also encourage you to join our community of founders at the Founders Alliance group on Facebook.

SAFEs and convertible notes

Dilution can be somewhat more complicated in the case of convertible notes or SAFEs (Simple Agreements for Future Equity). That's because you haven't agreed on what they're worth at the time of investment. For simplicity, I will refer to both as "SAFEs" going forward.

SAFEs are an agreement to convert into equity the next time you raise a priced round selling equity. The lead investor of that round will set the valuation and terms of the investment.

There are two flavors of SAFEs, capped and un-capped.

An uncapped SAFE converts to equity at a discount to the next round. If your priced round is at a pre-money valuation is $10 million. Then investors with a 20% discount get to convert at $8 million. The discount is there because they took a higher risk by investing earlier than the people in this priced round.

Most investors resist un-capped notes because it might be a very long time between when they invested and that priced round. They worry about a situation where they take a massive risk by investing early. Then you use those funds to grow the company by a factor of ten.

Without a cap, they're converting at a small discount to this high valuation. They are paying much more than they would have if they negotiated a fixed valuation back when they invested.

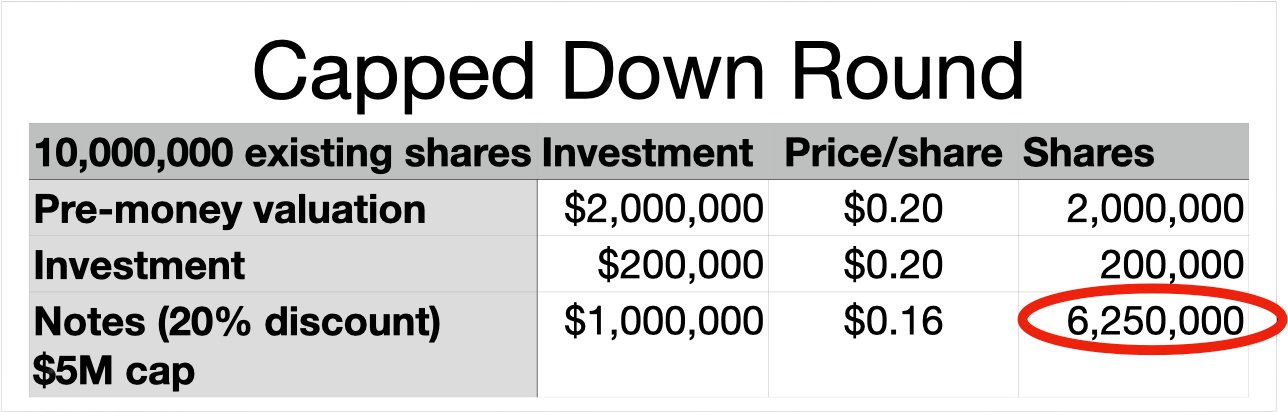

A cap sets a maximum valuation for that conversion. With a cap, the SAFE says that the investor will convert at a 20% discount to the next round, but at a valuation no higher than $5 million. If the priced round is at $10M, they get to convert at $5M rather than $8M.

Things get complicated when you're converting at far below the expected value. Suppose you raised $1 million on a SAGE with a $5 million cap. Everyone hopes the company will do well, so in their heads, this deal is effectively happening at $5 million.

But, if the company struggles to execute and starts to run low on funds, the next round might come in at a $2M valuation. Instead of getting 2 million shares, they now convert at a discount to the actual price and receive over 6 million shares.

In some cases, a down round can pass majority ownership to the SAFE holders.

This is one reason to consider doing a priced round for equity rather than a SAFE, even though it's somewhat more complicated.

Pre-money vs. post-money valuations

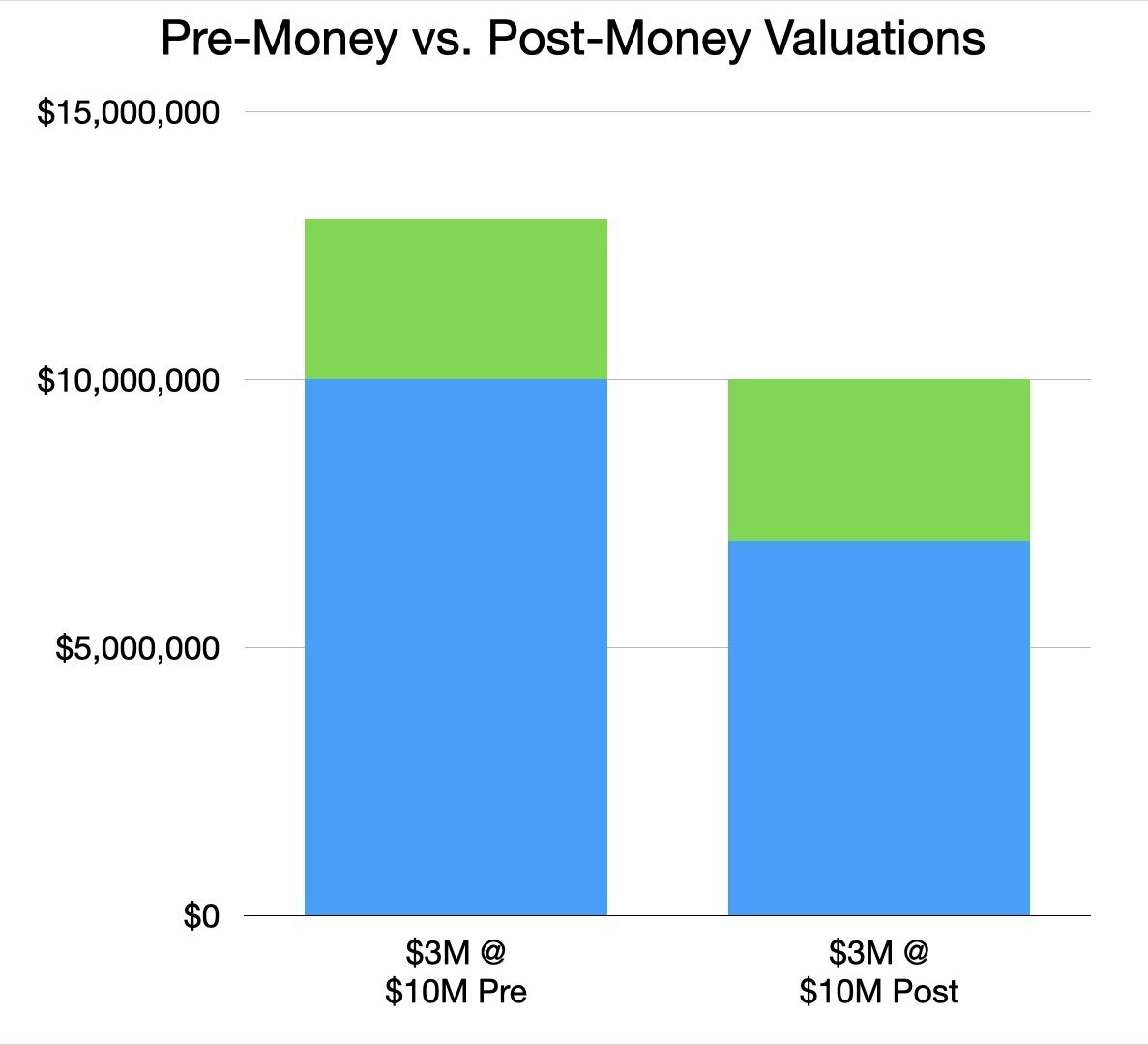

When you're discussing the valuation of your company, the results can be very different if that number is pre-money vs. post-money.

With pre-money, we agree that your company is worth $10M now, so if someone invests $1 million to it, you're now worth $11 million.

With post-money valuations, we agree your company is worth $10 million after receiving the $1 million investment. Therefore it's only worth $9 million now. That's a meaningful difference.

However, in many cases, you don't know how much money you will be taking in this round. You might oversubscribe or raise multiple rounds of SAFEs. With a post-money valuation, you won't know what your part of the company is worth until everything converts, and the round closes.

With post-money valuations, the more money you bring in, the lower the value of your stock will be. The graph shows this for a situation where you are raising a $3 million round at a $10 million pre- vs. post-money valuation.

Of course, in reality, you would negotiate a different valuation based on which type you were using, but if the total is very uncertain, this can be difficult.

Anti-dilution terms

Founders are not the only people worried about dilution. Investors are concerned about dilution too.

Once investors receive their stock, any future fundraising or new stock options will dilute them right along with you.

Some investors try to put anti-dilution provisions into the term sheet. There are several kinds of anti-dilution protection ranging from relatively benign to extremely aggressive.

If an investor simply wants to maintain their percentage ownership in the company, they may request pro-rata investment rights. That means they have the option to take a fraction of future rounds equal to their ownership percentage in the company. For example, if someone owns 10% of your startup, and you are raising a $10 million round, they have the right to invest $1 million in that round.

Some investors will request super-pro-rata rights, which gives them the right to increase their ownership percentage over time. This can cause problems for future investors who might not hit their ownership targets if the earlier investors fully exercise their rights. These rights are considered relatively aggressive, and you should avoid them if at all possible.

The biggest threat to investors comes in down rounds, which could wipe out most of their value in the company. To protect against that, they may request anti-dilution protection that effectively revalues their investment to soften the blow.

The most extreme form of this is called "full ratchet," which effectively rewrites history as though the investor had happened at the new lower valuation.

Suppose a VC invests $2 million in your A-round at $10 per share, giving them 200,000 shares. Later, after some difficulties, another VC invests $500,000 at $2 per share. With a full ratchet, the first VC is treated as though they also invested at $2 per share, so they now effectively own one million shares. This is very bad for the founders and may also frighten off that new VC.

Other forms of anti-dilution are less aggressive, like "weighted-average," which adjusts the revaluation based on the size of the new round. But, they are still quite founder hostile.

Bootstrapping vs. VC

Considering all the ways your ownership can dwindle, is taking outside investment the best choice?

Many companies achieve stellar outcomes while taking little or no outside money. However, most unicorns and decacorns ($1 billion and $10 billion valuation companies) are VC-funded.

Because round after round of outside investment can reduce your ownership to a small fraction of the company, your exit needs to be proportionately larger to deliver you the same result.

Essentially bootstrapped companies frequently exit at around $100 million. After employee options and possibly some early angel investments, founders could walk away with $50-$70 million.

To achieve the same result for the founders, a company that raised pre-seed through D rounds might have to exit at $500 million to $1 billion.

Whether to take all that funding depends on your confidence of being able to hit those stratospheric valuations. Once you start taking VC funds, nothing less will be acceptable.

If you stick with bootstrapping, you have the option to take a much smaller but still highly lucrative exit. The downside is that other companies might swoop in and snatch your market while you are still small, or you won't be able to reach the scale required for network effects to kick in.

Here is a simple tool for calculating dilution when you issue new stock from Neoschronos.

This capital calculator from Founders Workbench lets you compare a few different scenarios.

Updated Dec 12, 2022, to fix an error. The discount should have been 20% not 10%

Next, you might want to read about how high valuations can hurt your startup: