74. What is a Cap Table? 🧐 Tracking VC Investments and stock option grants

YouTube video version of this article

Many new founders are confused about how cap tables, stock, and dilution work. This puzzlement comes about because stock works very differently in startups than in the public markets we are more familiar with.

This article provides an overview of how capitalization and equity function in startups so you can talk intelligently to your attorneys, investors, co-founders, and employees.

I want to share the most critical advice up-front: Always have a lawyer experienced with startups review your cap-table and all documents related to equity and ownership. Mistakes on your cap-table and arguments over ownership can be catastrophic for your company.

Startup Stock

Let's start with the big picture. Stock represents ownership in a company. Each share of stock is one small slice of the whole company.

When you buy shares in the stock market, you usually purchase them from other owners. This is called the secondary market. That is not how things typically work in a startup.

Companies create the stock they sell to investors from nothing. The board and existing shareholders simply declare that more stock exists, so it does.

Most companies create several flavors of stock, called "series." You may see people talk about Series Seed or Series A rounds. That describes the kind of stock being sold in that funding round. Typically, companies create a new series of stock for each priced round.

Common stock is the only stock that exists when you first create your company.

Authorized, Issued, Outstanding, and Reserved

Shares in your company can exist in four different states. Understanding how and when shares are counted based on their status is critical.

Authorized shares are the total number of shares the company is allowed to create. This amount is written into the company's articles of incorporation. When you need to authorize more shares or create new series of shares, you do so by amending the articles. However, just because shares have been authorized does not mean they are owned by anyone or even exist.

Issued shares are all the shares owned by someone. That could be the founders, employees, or investors. Your company can even own issued shares if it bought back some of your stock. Company-owned stock is called "treasury shares," but they rarely come up with early-stage startups.

Outstanding shares are similar. They consist of all the stock owned by anyone but the company. The number of outstanding shares is the number of issued shares minus the treasury shares.

The final category is reserved shares. These are authorized shares that have not been given to anyone but have been obligated in some way. Reserved shares work like an escrow account, ensuring the shares are available when needed. The most common type of reserved shares is your options pool. Without a reserved stock pool, the company might come up short if all the employees exercised their options. Another frequent use of reserved shares is for warrants.

Common vs. preferred stock

The differences between common and preferred stock deserve their own episode. For this high-level overview of equity, I will just give you the highlights.

Common stock is the most "vanilla" kind of share. It is created first and typically issued to the founders and employees through direct grants and incentive options. It has no liquidation preferences or special rights.

Once you start bringing in investors, they will likely want some additional protection. That means preferred stock. However, in some cases, investors may ask for common stock instead. Certain countries, like the UK, provide substantial subsidies and tax benefits to seed investors who take common stock. In the absence of those incentives, investors almost always demand preferred stock. The lead investor in each round will negotiate the exact nature of the preferred stock.

The most significant difference between common and preferred stock is the "preference." That is an amount of money paid to the investor in a liquidation before any other shareholders. The amount is usually expressed as a multiple of the initial investment. A "two times" preference means the company pays the investor twice their investment. Generally, the last money in has precedence over earlier investors. They get paid their preference first, then the next most recent investor, and so on, until the remaining funds, if any, are shared among the common stockholders.

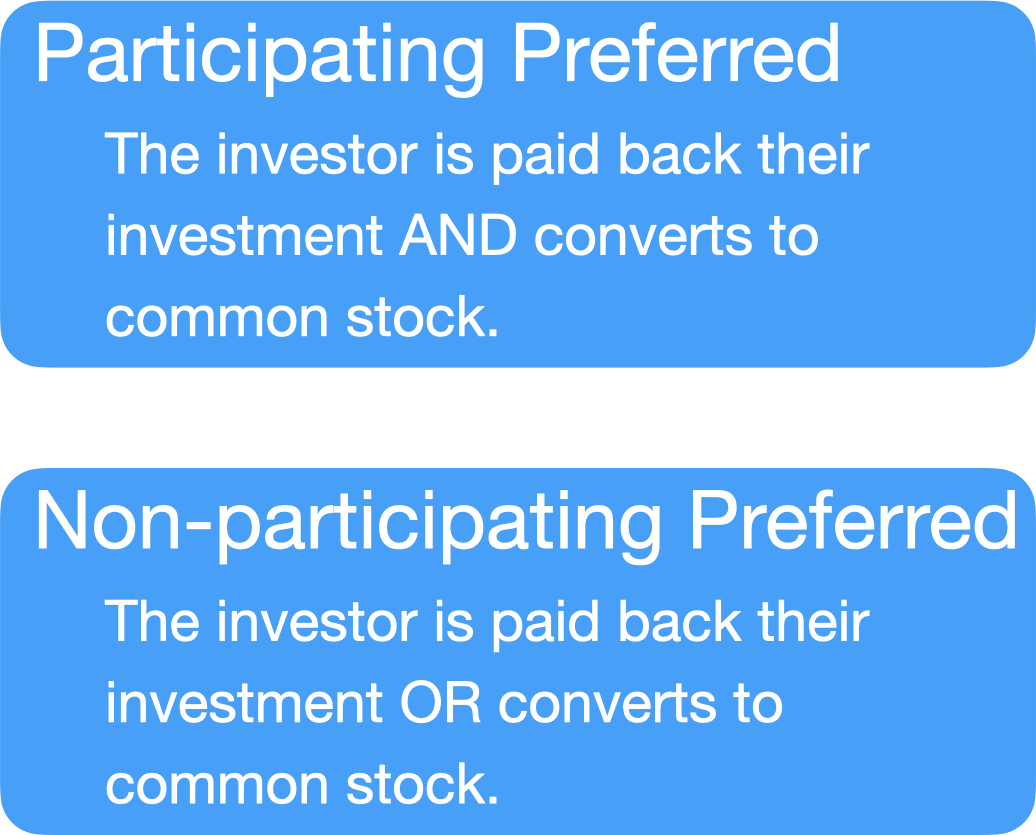

There are two kinds of preferences: participating and non-participating.

With participating preferred stock, in an acquisition or liquidation, the holder first receives their preference payout, then converts those shares to common stock and receives their share of the remaining funds.

Holders of non-participating stock need to make a choice. They can either receive the preference payout or convert to common and receive their share of the proceeds. In a positive outcome like an acquisition at a high valuation, all the preferred stockholders would convert. The preferences only come into play when the company is liquidated in a fire sale.

Avoid participating preferred stock if at all possible.

Fully Diluted Shares

One term that you're likely to run into as soon as you start working with investors is fully diluted shares. That's the number used to calculate the per-share price of your company.

The number of fully diluted shares equals the number of outstanding shares plus all the reserved shares.

The significance is that the board, without the consent of the shareholders, could issue options for every share in the options pool and warrants for all the shares in the warrant pool. Then all those people could exercise those instruments, converting them to stock. To value the shares, the investors assume all that could happen, so they use the pre-money valuation divided by the number of Fully Diluted shares to calculate the price per share.

In most cases, you don't include convertible notes and SAFEs because you don't know how many shares they will become until you close a round that will trigger their conversion. Until then, the effective share price for those investors is undetermined. These investments still need to be tracked alongside your cap table, but they are not actual shares yet.

Options

Although the options pool is on your cap table, the options you grant are not. Nevertheless, you need to track them in detail and provide at least a summary to potential investors.

For every option grant, you need to record the:

Recipient

Number of options granted

Grant Date

Strike price

Vesting Schedule

Expiration date

Managing the cap-table

Keeping track of all this information can get complicated, particularly once you have several investors and employees.

You can certainly do it all on a spreadsheet, and there are many templates available for download. Going through the exercise of setting up your cap-table and running some scenarios for various outcomes can be educational.

However, I don't recommend managing your official cap-table yourself. There are many subscription services that can help ensure you don't make any mistakes.

Even innocent mistakes on the cap-table can be devastating, leading to epic legal fights and scaring off potential investors.

I don't have any specific suggestions for cap-table management tools because it is a fast-evolving space. Some quick searching will surface the current best options. There are many good choices at reasonable prices.

In addition to the cap-table itself, you need to track the SAFE or convertible notes, options, and warrants. You also need to have ready access to all associated board actions, shareholder votes, investor agreements, option agreements, etc. During due diligence, investors will probably require you to show documentation of every entry related to corporate ownership.

Even using a tool to manage this information, you should still have your experienced attorney review it. That outside set of eyes can turn up mistakes or omissions and demonstrates good faith in trying to have the most accurate picture of the company's capitalization.

The cap-table at incorporation

To see how cap-tables develop, let's look at a hypothetical startup at a few different points in its evolution, starting the moment after incorporation.

This is the simplest your cap-table will ever be. There are only entries for the initial stock issued to each of the founders.

In this example, the company initially authorized ten million shares of common stock and issued three million to one founder and three million to the other. Leaving five million shares authorized but not issued and five million fully diluted shares. Founder 1 owns 60% of the company, and Founder 2 owns 20%. The un-issued shares do not come into the calculation.

All of these numbers are entirely arbitrary. You can authorize as many shares as you want and divide up the issued shares between the founders in any way you negotiate among yourselves.

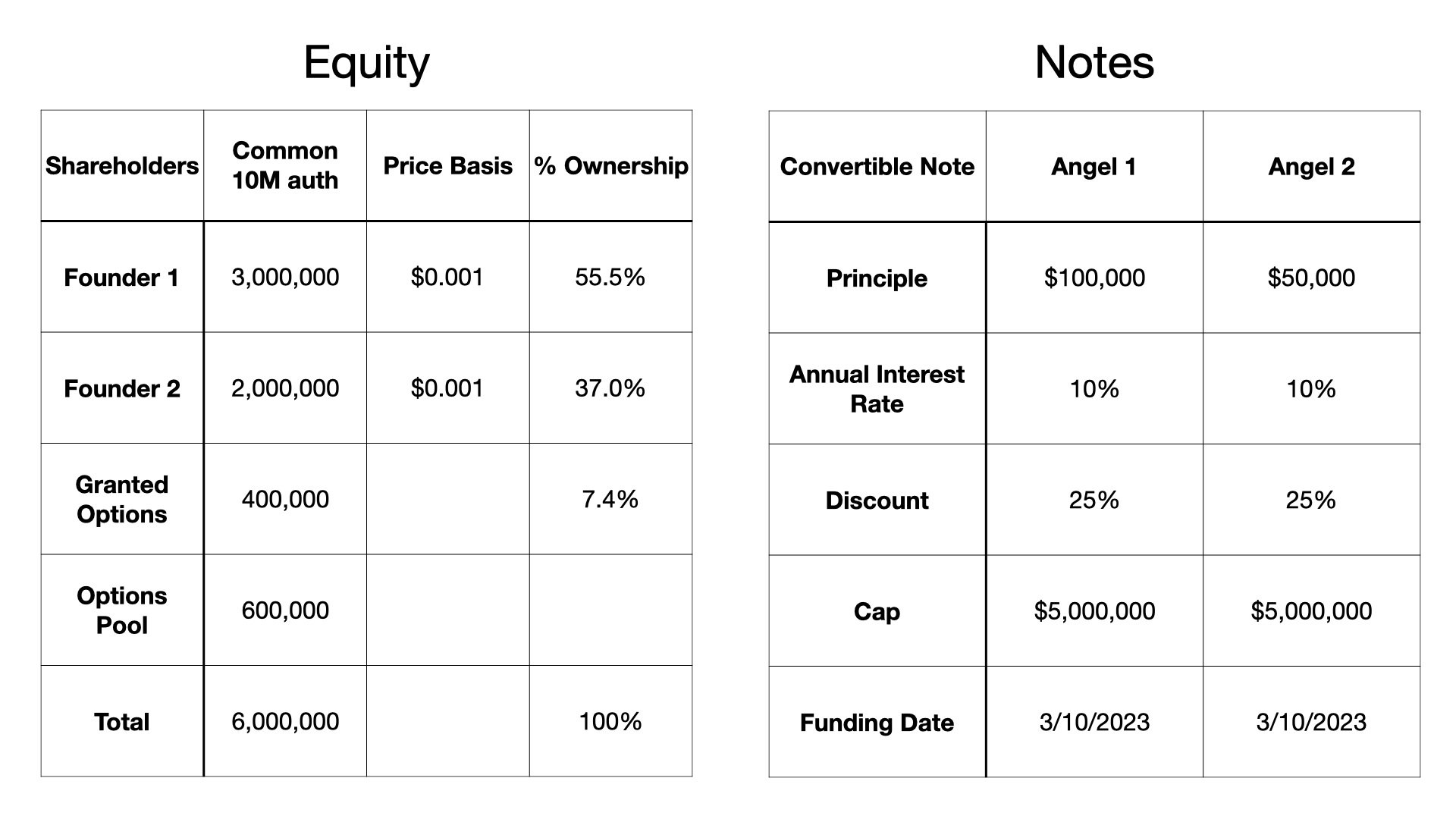

After the angel round

Let's fast forward a year. The company has made good progress, hired some employees, and granted them options. The company also raised money from two angel investors on a convertible note.

Because they created a two million share options pool, there are now six million fully diluted shares. That has changed the effective ownership of the company, although none of those option shares has been issued, so the voting power is unchanged.

The company has already granted 400,000 options from the option pool, leaving 600,000 available for future grants.

You can see that the company is tracking the investors alongside the cap table, but at the moment, they don't own any stock. This information is critical for future investors to understand how the ownership will change following a conversion event.

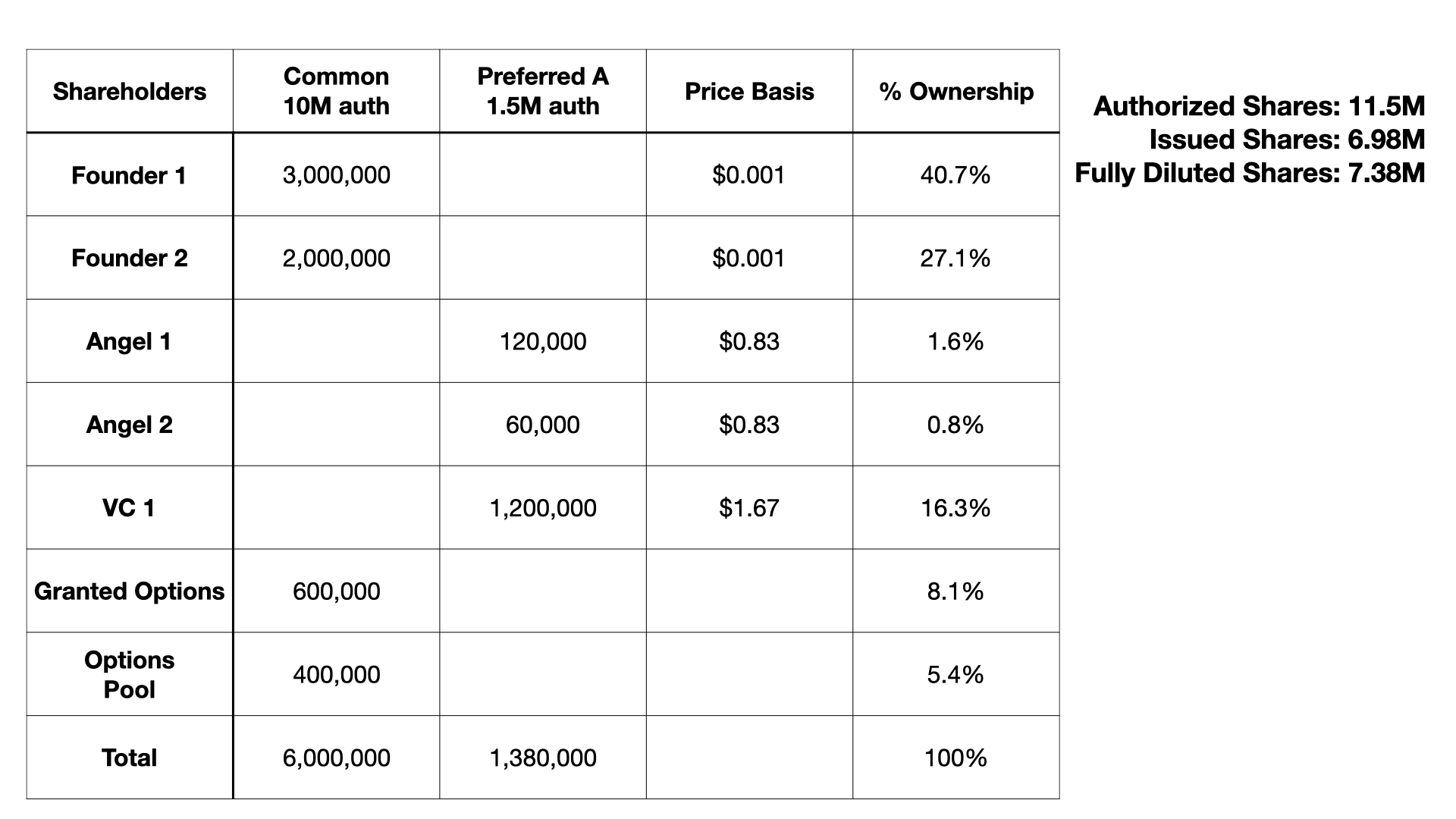

After the A-Round

A year later, the company closed a priced round selling Series A preferred stock. Note, they could have called this series Seed or anything else. The names are customary but not meaningful.

Now there are two kinds of stock on the cap table because the shareholders have authorized the creation of up to 1.5 million shares of Series A stock. However, in this round, they only issued 1,380,000 shares.

The venture capital investor negotiated the terms of the preferred stock they received, and the angel investors automatically converted into that same kind of stock, but at a different price. In this example, the new investment was at a $10 million pre-money valuation. Because the angels had a $5 million cap on their notes, they received stock at half the price per share as the VC.

The company has also issued more options. It now has 600,000 options granted and only 400,000 available in the pool. This is low enough that many investors would have required the company to increase the pool, but I am ignoring that complexity for this example.

Each time the company creates a new series of stock, the cap-table gets a new column to track it. If an investor participates in multiple rounds, they might appear several times with different series of stock purchased at different prices.

When calculating the fully diluted shares, you count the preferred shares as though they had converted to common. Initially, common and preferred shares typically convert on a one-to-one basis. However, stock splits, anti-dilution adjustments, and other factors can change the ratio. No matter the conversion factor, the fully diluted number is always calculated based on the as-converted number of common shares.

Take Away

This is just a high-level overview of startup capitalization. It should help you speak intelligently on the topic, but it is not enough to make you an expert.

My best advice is to always use a tool and have a lawyer check your work. The consequences of errors are dire.

If something here was confusing, or you have additional questions, please ask in the comments below. I will either answer there or update this article based on your feedback.

This article is part of the series on Founder Insights.

Feel the Boot also has articles on Getting Started, Pitching, Fundraising, Running the Business, and interviews with founders and experts. I hope you find them helpful as you build your startup.

Until next time, Ciao!