10. Understanding how and why to leverage stock options in your startup

Options are one of the more complex and poorly understood issues facing new entrepreneurs. Many founders have only a general idea of how they work, often from receiving them in past jobs. Knowing how to manage and deploy options can make a big difference in employee retention and the dilution of founder ownership.

This article is part of our series on Running your Business. It is a companion piece to Stock Options Explained, which will help you educate your employees on the value of options..

Legal disclaimer: I am neither a lawyer nor an accountant. This is general information, not tax or financial advice.

When a company grants options, they are giving someone the right to buy up to some amount of stock, at a particular price (the strike price), within a period of time. For example, you might want to offer options as a hiring bonus to a new senior developer, granting them the option to buy one million shares at one dollar per share at any time within the next ten years.

Businesses issue options to employees, contractors, board members, and the like for specific purposes. First, it aligns the interests of management, investors, and workers who all stand to benefit substantially from an increase in the value of the company. Second, it allows the company to pay less cash for salaries, and money is often in very short supply for early-stage businesses. Third, companies can use it to reward high performing and high impact workers. Fourth, options compensate early employees for taking the substantial risk of joining a startup.

Before a company can issue options, it needs to create an option plan which spells out the legal structure of the options and establishes an option pool. Shareholders need to approve any new option plans, while the Board of Directors can authorize the granting of options. The CEO can’t do either of these on their own. Very early on, you might be CEO, the entirety of the board, as well as the majority shareholder. You might be able to have all the votes by your self in a room, but you need to put on each of the hats separately to ensure the process is legal and binding.

Deciding how many shares to set aside for the option pool can be one of the most confounding choices for founders. When creating or updating an option plan, companies must pre-allocate a block of shares against which options are later issued. As an example, if the company wants to grant one million options right away, it might create a pool of two million shares, so they can grant up to another million options before needing to increase the pool. The pool must hold enough shares to handle every option converting to stock at that moment. A good rule of thumb is that tech startups should allocate between 10% and 20% of the total value of the company to the option pool.

Often options pools are adjusted during a funding round. Investors will generally ask the company to significantly increase the pool before the investment. In this negotiation, existing shareholders and investors have opposing interests. The shareholders usually want to keep the pool as small as possible to minimize their dilution. Investors want the company to maximize the pool before they invest, to minimize post-investment pool increases, which would dilute them along with the founders and earlier investors. Let’s look at an example to see how that works.

Suppose that the company has a pre-money valuation of $10M, and has issued 10M shares. That sounds like the share price should be $1. However, the share price is usually calculated based on the fully diluted number of shares, which includes the whole option pool (not just issued options). One reason for this is that once the pool is established, the BoD can issue options without further shareholder approval.

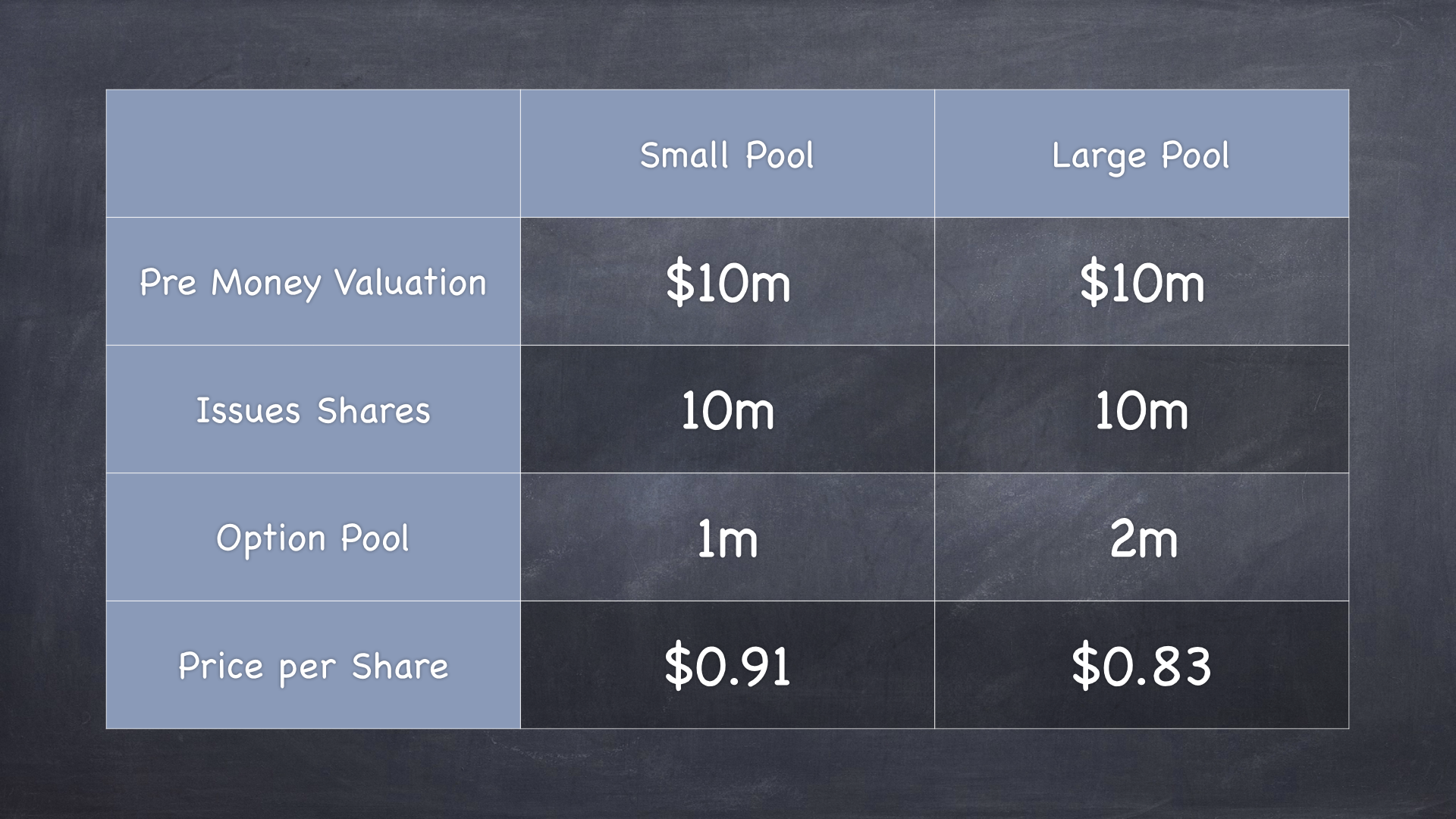

Consider the investment with either a 1 million share option pool (as the founder would like) or a two million share pool (which the investor is requesting).

With a one million share pool, there are 11 million fully diluted shares, which means the share price is actually $0.91. However, with a two million share pool, the investor only pays $0.83 per share, roughly 10% less.

Everyone involved wants enough options available to recruit and keep the best people, the debate concerns when to increase the pool rather than by how much. A good compromise is to increase the option pool enough to comfortably last through all expected grants to new hires and existing employees before the next planned round of funding.

So, how many options should a company grant to an employee? The actual number of options is misleading. A better perspective is to look at the net present value and implied ownership in the company. For a startup, after the first few employees, typical grants are small fractions of a percent of the company, except for C-Suite hires.

Once the company has a track record of valuations and volatility, the grants can be valued based on standard option contract pricing using the Black-Scholes equation. There are lots of calculators online to help with that.

Before that track record is available, a common assumption is that the volatility of a very early stage company is 125%-150%, dropping to 100% around series A. It turns out that a 150% volatility suggests the options are worth roughly their strike price.

When talking to employees, I like to also talk about possible value at exit. By looking at comparable company exits, you can make a reasonable argument as to what those options would be worth in a similar exit based on the fraction of the company owned.

If founders are confused about options, many employees are completely in the dark. I have seen people brag that they have millions of options while scoffing at someone else at a different company who had only thousands. That is nonsense because the raw number says nothing about the value of the options and the ownership they represent.

However, it is essential to understand this psychological reality. Early in my company, I gave an employee something like 100 options, which was a substantial grant. However, they looked unhappy because the number was so small. My solution was quick, simple, and effective. I did a thousand to one stock split, so the grant was now for one hundred thousand options. It was precisely the same grant in terms of value and as a percentage of the company, but now the employee was much happier.

Your stock option plan should always include a vesting schedule. Vesting protects the company if the relationship with the grantee changes. For example, if the company fires them shortly after they start, the options stop vesting automatically. This allows a business to be generous with grants to a new employee while still being protected if they don’t work out. Typically options vest over four years, with 25% vesting at the end of the first year and the rest monthly after that.

I have seen many cases where someone was hired with high hopes and expectations (and a big option grant) only to find that it was not going to work out. If they had not used a vesting schedule, that now former employee (who had contributed almost nothing) would end up owning a meaningful chunk of the company.

Finally, stock option plans should support both of the main kinds of options: Incentive stock options (ISO) for employees, and Non-Qualified Options (NSO) for other people like advisors and directors.

When everything goes well, options are a big win for everyone involved, founders, employees, and investors.

I would love to know what topics you would like to see covered next. Please let me know in the comments.

Till next time … Ciao!

Next, I encourage you to look at this article on how to explain the value of options to your employees.